Was Rock and Roll Responsible for Americaã¢â‚¬â„¢s Traditional Family, Sexual, and Racial Customs

| Rock and roll | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins |

|

| Cultural origins | Late 1940s – early on 1950s, United states of america |

| Derivative forms |

|

| Regional scenes | |

| |

| Other topics | |

| |

Rock and gyre (frequently written as stone & curl, rock 'n' roll, or stone 'n whorl) is a genre of pop music that evolved in the United States during the late 1940s and early 1950s.[ane] [2] [ page needed ] It originated from black American music such equally gospel, jump blues, jazz, boogie woogie, rhythm and dejection,[3] as well as country music.[4] While rock and curl's formative elements can be heard in blues records from the 1920s[5] and in country records of the 1930s,[4] the genre did not learn its name until 1954.[half dozen] [ii]

According to announcer Greg Kot, "rock and curlicue" refers to a style of pop music originating in the United States in the 1950s. Past the mid-1960s, rock and curl had developed into "the more than encompassing international style known as rock music, though the latter also continued to be known in many circles as rock and coil."[7] For the purpose of differentiation, this article deals with the kickoff definition.

In the primeval stone and roll styles, either the piano or saxophone was typically the lead instrument. These instruments were generally replaced or supplemented by guitar in the middle to late 1950s.[8] The vanquish is substantially a dance rhythm[9] with an accentuated backbeat, almost e'er provided by a snare drum.[ten] Classic stone and roll is usually played with one or two electric guitars (one lead, one rhythm) and a double bass (string bass). Later the mid-1950s, electric bass guitars ("Fender bass") and drum kits became popular in classic stone.[8]

Rock and roll had a polarizing influence on lifestyles, fashion, attitudes, and language. It is frequently depicted in movies, fan magazines, and on television. Rock and roll is believed by some to have had a positive influence on the civil rights movement, because both Black American and White American teenagers enjoyed the music.[11]

Terminology [edit]

The term "rock and roll" is defined past Greg Kot in Encyclopædia Britannica equally the music that originated in the mid-1950s and later adult "into the more than encompassing international mode known as rock music".[7] The term is sometimes also used as synonymous with "rock music" and is defined equally such in some dictionaries.[12] [xiii]

The phrase "rocking and rolling" originally described the movement of a send on the sea,[14] but by the early 20th century was used both to draw the spiritual fervor of blackness church building rituals[fifteen] and equally a sexual illustration. A retired Welsh seaman named William Fender can be heard singing the phrase "rock and gyre" when describing a sexual run across in his operation of the traditional song "The Baffled Knight" to the folklorist James Madison Carpenter in the early 1930s, which he would take learned at sea in the 1800s; the recording can be heard on the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library website.[16]

Various gospel, blues and swing recordings used the phrase before it became widely popular; it was used in 1940s recordings and reviews of what became known every bit "rhythm and blues" music aimed at a black audition.[15]

In 1934, the song "Rock and Roll" by the Boswell Sisters appeared in the film Transatlantic Merry-Become-Round. In 1942, before the concept of stone and roll had been divers, Billboard magazine columnist Maurie Orodenker started to use the term to describe upbeat recordings such as "Rock Me" by Sis Rosetta Tharpe; her style on that recording was described as "rock-and-roll spiritual singing".[17] [18] By 1943, the "Rock and Roll Inn" in Southward Merchantville, New Jersey, was established every bit a music venue.[19] In 1951, Cleveland, Ohio, disc jockey Alan Freed began playing this music mode, and referring to it as "rock and roll"[twenty] on his mainstream radio programme, which popularized the phrase.[21]

Several sources suggest that Freed found the term, used as a synonym for sexual intercourse, on the record "Lx Minute Man" by Billy Ward and his Dominoes.[22] [23] The lyrics include the line, "I stone 'em, roll 'em all dark long".[24] Freed did not acknowledge the suggestion about that source in interviews, and explained the term every bit follows: "Rock 'n ringlet is really swing with a modern proper noun. It began on the levees and plantations, took in folk songs, and features blues and rhythm".[25]

In discussing Alan Freed's contribution to the genre, two significant sources emphasized the importance of African-American rhythm and blues. Greg Harris, then the Executive Director of the Stone n Roll Hall of Fame, offered this annotate to CNN: "Freed's role in breaking down racial barriers in U.S. popular culture in the 1950s, by leading white and black kids to listen to the same music, put the radio personality 'at the vanguard' and made him 'a really important figure'".[26] After Freed was honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, the organization's Web site offered this annotate: "He became internationally known for promoting African-American rhythm and blues music on the radio in the Us and Europe nether the proper name of stone and whorl".[27]

Not often acknowledged in the history of rock and ringlet, Todd Storz, the owner of radio station KOWH in Omaha, Nebraska, was the kickoff to adopt the Top 40 format (in 1953), playing only the nigh popular records in rotation. His station, and the numerous others which adopted the concept, helped to promote the genre: by the mid 50s, the playlist included artists such as "Presley, Lewis, Haley, Berry and Domino".[28] [29]

Early rock and roll [edit]

Origins [edit]

The origins of stone and whorl have been fiercely debated by commentators and historians of music.[30] There is full general agreement that it arose in the Southern United States – a region that would produce most of the major early rock and roll acts – through the meeting of diverse influences that embodied a merging of the African musical tradition with European instrumentation.[31] The migration of many former slaves and their descendants to major urban centers such as St. Louis, Memphis, New York City, Detroit, Chicago, Cleveland, and Buffalo meant that black and white residents were living in close proximity in larger numbers than ever before, and as a outcome heard each other's music and even began to emulate each other's fashions.[32] [33] Radio stations that fabricated white and black forms of music available to both groups, the development and spread of the gramophone record, and African-American musical styles such as jazz and swing which were taken upwardly past white musicians, aided this procedure of "cultural collision".[34]

The immediate roots of rock and whorl lay in the rhythm and dejection, then called "race music",[35] in combination with either Boogie-woogie and shouting gospel[36] or with land music of the 1940s and 1950s. Specially pregnant influences were jazz, dejection, gospel, country, and folk.[30] Commentators differ in their views of which of these forms were nigh important and the degree to which the new music was a re-branding of African-American rhythm and blues for a white market place, or a new hybrid of black and white forms.[37] [38] [39]

In the 1930s, jazz, and especially swing, both in urban-based dance bands and blues-influenced land swing (Jimmie Rodgers, Moon Mullican and other similar singers), were among the first music to present African-American sounds for a predominantly white audience.[38] [40] 1 particularly noteworthy instance of a jazz vocal with recognizably rock and roll elements is Big Joe Turner with pianist Pete Johnson'due south 1939 unmarried Roll 'Em Pete, which is regarded as an important precursor of rock and roll.[41] [42] [43] The 1940s saw the increased use of blaring horns (including saxophones), shouted lyrics and boogie woogie beats in jazz-based music. During and immediately afterwards World War II, with shortages of fuel and limitations on audiences and available personnel, big jazz bands were less economic and tended to be replaced by smaller combos, using guitars, bass and drums.[30] [44] In the same period, particularly on the Westward Coast and in the Midwest, the evolution of bound blues, with its guitar riffs, prominent beats and shouted lyrics, prefigured many later developments.[thirty] In the documentary picture show Hail! Hail! Rock 'n' Coil, Keith Richards proposes that Chuck Drupe developed his brand of rock and roll by transposing the familiar two-note atomic number 82 line of jump blues pianoforte directly to the electric guitar, creating what is instantly recognizable as rock guitar. This proposal past Richards neglects the black guitarists who did the same thing before Berry, such every bit Goree Carter,[45] Gatemouth Brown,[46] and the originator of the style, T-Bone Walker.[47] State boogie and Chicago electric blues supplied many of the elements that would be seen as feature of rock and roll.[30] Inspired by electric blues, Chuck Berry introduced an aggressive guitar audio to rock and whorl, and established the electric guitar equally its centerpiece,[48] adapting his rock band instrumentation from the basic blues band instrumentation of a lead guitar, second chord instrument, bass and drums.[49] In 2017, Robert Christgau declared that "Chuck Drupe did in fact invent rock 'n' whorl", explaining that this artist "came the closest of whatever single effigy to being the i who put all the essential pieces together".[50]

Beak Haley and his Comets performing in the 1954 Universal International picture Round Up of Rhythm

Stone and roll arrived at a time of considerable technological modify, shortly after the development of the electric guitar, amplifier and microphone, and the 45 rpm record.[thirty] There were also changes in the record industry, with the rise of independent labels like Atlantic, Sun and Chess servicing niche audiences and a similar ascent of radio stations that played their music.[30] It was the realization that relatively affluent white teenagers were listening to this music that led to the development of what was to be divers every bit rock and roll as a distinct genre.[30] Because the development of stone and roll was an evolutionary process, no single record can be identified as unambiguously "the first" rock and roll tape.[two] Contenders for the title of "first rock and curlicue record" include Sis Rosetta Tharpe's "Foreign Things Happening Every Day" (1944),[51] "That's All Right" by Arthur Crudup (1946), "Move It On Over" past Hank Williams (1947),[52] "The Fat Man" past Fats Domino (1949),[2] Goree Carter's "Rock Awhile" (1949),[53] Jimmy Preston's "Rock the Joint" (1949), which was afterwards covered by Bill Haley & His Comets in 1952,[54] "Rocket 88" by Jackie Brenston and his Delta Cats (Ike Turner and his band The Kings of Rhythm), recorded by Sam Phillips for Sun Records in March 1951.[55] In terms of its wide cultural impact across society in the The states and elsewhere, Bill Haley'southward "Stone Around the Clock",[56] recorded in April 1954 but not a commercial success until the following year, is generally recognized as an important milestone, but it was preceded past many recordings from before decades in which elements of stone and gyre can exist clearly discerned.[2] [57] [58]

Other artists with early rock and roll hits included Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, Petty Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Gene Vincent.[55] Chuck Berry's 1955 classic "Maybellene" in particular features a distorted electrical guitar solo with warm overtones created by his minor valve amplifier.[59] However, the use of distortion was predated by electrical blues guitarists such as Joe Hill Louis,[sixty] Guitar Slim,[61] Willie Johnson of Howlin' Wolf'southward band,[62] and Pat Hare; the latter two as well made use of distorted power chords in the early 1950s.[63] Also in 1955, Bo Diddley introduced the "Bo Diddley trounce" and a unique electrical guitar style,[64] influenced past African and Afro-Cuban music and in turn influencing many later artists.[65] [66] [67]

Rhythm and blues [edit]

Stone and roll was strongly influenced past R&B, according to many sources, including an article in the Wall Street Periodical in 1985 titled, "Rock! It's Nevertheless Rhythm and Blues". In fact, the author stated that the "ii terms were used interchangeably", until nigh 1957. The other sources quoted in the article said that stone and ringlet combined R&B with pop and country music.[68]

Fats Domino was ane of the biggest stars of rock and roll in the early 1950s and he was non convinced that this was a new genre. In 1957, he said: "What they phone call rock 'due north' roll now is rhythm and blues. I've been playing it for 15 years in New Orleans".[69] Co-ordinate to Rolling Stone, "this is a valid statement ... all Fifties rockers, blackness and white, country built-in and city-bred, were fundamentally influenced past R&B, the blackness popular music of the belatedly Forties and early Fifties".[seventy] Farther, Niggling Richard built his ground-breaking audio of the same era with an uptempo blend of boogie-woogie, New Orleans rhythm and dejection, and the soul and fervor of gospel music voice.[36]

Rockabilly [edit]

"Rockabilly" commonly (only not exclusively) refers to the type of rock and coil music which was played and recorded in the mid-1950s primarily by white singers such as Elvis Presley, Carl Perkins, Johnny Greenbacks, and Jerry Lee Lewis, who drew mainly on the country roots of the music.[71] [72] Presley was greatly influenced and incorporated his style of music with some of the greatest African American musicians like BB King, Arthur Crudup and Fats Domino. His style of music combined with blackness influences created controversy during a turbulent time in history.[72] Many other popular rock and roll singers of the fourth dimension, such as Fats Domino and Footling Richard,[73] came out of the black rhythm and blues tradition, making the music attractive to white audiences, and are not usually classed as "rockabilly".

Presley popularized rock and whorl on a wider scale than any other single performer and by 1956, he had emerged as the singing awareness of the nation.[74]

Bill Flagg who is a Connecticut resident, began referring to his mix of hillbilly and rock 'n' curl music as rockabilly around 1953.[75]

In July 1954, Presley recorded the regional hit "That's All Right" at Sam Phillips' Sun Studio in Memphis.[76] Three months earlier, on April 12, 1954, Nib Haley & His Comets recorded "Rock Around the Clock". Although only a small hit when first released, when used in the opening sequence of the motion-picture show Blackboard Jungle a year later, information technology gear up the rock and scroll boom in motion.[56] The song became ane of the biggest hits in history, and frenzied teens flocked to see Haley and the Comets perform it, causing riots in some cities. "Rock Around the Clock" was a quantum for both the group and for all of rock and curl music. If everything that came before laid the background, "Rock Around the Clock" introduced the music to a global audition.[77]

In 1956, the inflow of rockabilly was underlined past the success of songs like "Folsom Prison Blues" past Johnny Greenbacks, "Blue Suede Shoes" past Perkins and the No. i hit "Heartbreak Hotel" by Presley.[72] For a few years it became the virtually commercially successful form of rock and roll. After rockabilly acts, especially performing songwriters like Buddy Holly, would exist a major influence on British Invasion acts and particularly on the song writing of the Beatles and through them on the nature of later rock music.[78]

Doo wop [edit]

Doo-wop was one of the most popular forms of 1950s rhythm and blues, often compared with rock and gyre, with an emphasis on multi-part vocal harmonies and meaningless backing lyrics (from which the genre later on gained its proper name), which were usually supported with calorie-free instrumentation.[79] Its origins were in African-American vocal groups of the 1930s and 40s, such as the Ink Spots and the Mills Brothers, who had enjoyed considerable commercial success with arrangements based on close harmonies.[80] They were followed by 1940s R&B vocal acts such as the Orioles, the Ravens and the Clovers, who injected a stiff chemical element of traditional gospel and, increasingly, the energy of spring blues.[80] By 1954, as stone and roll was beginning to sally, a number of like acts began to cantankerous over from the R&B charts to mainstream success, frequently with added honking brass and saxophone, with the Crows, the Penguins, the El Dorados and the Turbans all scoring major hits.[80] Despite the subsequent explosion in records from doo wop acts in the afterwards '50s, many failed to chart or were one-hit wonders. Exceptions included the Platters, with songs including "The Nifty Pretender" (1955)[81] and the Coasters with humorous songs like "Yakety Yak" (1958),[82] both of which ranked among the most successful rock and roll acts of the era.[eighty] Towards the end of the decade there were increasing numbers of white, particularly Italian-American, singers taking up Doo Wop, creating all-white groups similar the Mystics and Dion and the Belmonts and racially integrated groups like the Del-Vikings and the Impalas.[eighty] Doo-wop would exist a major influence on vocal surf music, soul and early Merseybeat, including the Beatles.[80]

Cover versions [edit]

Many of the earliest white rock and roll hits were covers or partial re-writes of earlier black rhythm and dejection or blues songs.[83] Through the late 1940s and early 1950s, R&B music had been gaining a stronger beat and a wilder style, with artists such equally Fats Domino and Johnny Otis speeding up the tempos and increasing the backbeat to not bad popularity on the juke joint circuit.[84] Before the efforts of Freed and others, black music was taboo on many white-endemic radio outlets, but artists and producers quickly recognized the potential of rock and roll.[85] Some of Presley's early recordings were covers of black rhythm and dejection or blues songs, such as "That'southward All Right" (a countrified arrangement of a blues number), "Baby Let's Play House", "Lawdy Miss Clawdy" and "Hound Domestic dog".[86] The racial lines, however, are rather more than clouded by the fact that some of these R&B songs originally recorded by black artists had been written past white songwriters, such as the team of Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller. Songwriting credits were oftentimes unreliable; many publishers, record executives, and even managers (both white and black) would insert their proper noun as a composer in order to collect royalty checks.

Covers were customary in the music manufacture at the time; information technology was made particularly easy by the compulsory license provision of U.s. copyright law (still in effect).[87] Ane of the beginning relevant successful covers was Wynonie Harris's transformation of Roy Brown's 1947 original jump blues striking "Practiced Rocking Tonight" into a more showy rocker[88] and the Louis Prima rocker "Oh Babe" in 1950, as well as Amos Milburn's cover of what may accept been the starting time white stone and roll record, Hardrock Gunter's "Birmingham Bounciness" in 1949.[89] The most notable trend, nevertheless, was white pop covers of blackness R&B numbers. The more than familiar sound of these covers may have been more palatable to white audiences, there may have been an element of prejudice, simply labels aimed at the white marketplace also had much better distribution networks and were generally much more profitable.[90] Famously, Pat Boone recorded sanitized versions of songs recorded by the likes of Fats Domino, Lilliputian Richard, the Flamingos and Ivory Joe Hunter. Afterwards, every bit those songs became popular, the original artists' recordings received radio play as well.[91]

The cover versions were not necessarily straightforward imitations. For case, Nib Haley's incompletely bowdlerized cover of "Milk shake, Rattle and Gyre" transformed Big Joe Turner's humorous and racy tale of adult love into an energetic teen dance number,[83] [92] while Georgia Gibbs replaced Etta James's tough, sarcastic vocal in "Roll With Me, Henry" (covered equally "Dance With Me, Henry") with a perkier vocal more advisable for an audition unfamiliar with the song to which James's song was an answer, Hank Ballard'southward "Piece of work With Me, Annie".[93] Presley's rock and whorl version of "Hound Dog", taken mainly from a version recorded by the pop band Freddie Bell and the Bellboys, was very dissimilar from the blues shouter that Big Mama Thornton had recorded four years earlier.[94] [95] Other white artists who recorded cover versions of rhythm & blues songs included Gale Tempest [Smiley Lewis' "I Hear You Knockin'"], the Diamonds [The Gladiolas' "Petty Darlin'" and Frankie Lymon & the Teenagers' "Why Exercise Fools Autumn in Love?"], the Crew Cuts [the Chords' "Sh-Boom" and Nappy Brown's "Don't Be Angry"], the Fountain Sisters [The Jewels' "Hearts of Rock"] and the Maguire Sisters [The Moonglows' "Sincerely"].

Decline [edit]

Some commentators have suggested a decline of rock and roll in the tardily 1950s and early 1960s.[96] [97] The retirement of Little Richard to become a preacher (Oct 1957), the departure of Presley for service in the United States Army (March 1958), the scandal surrounding Jerry Lee Lewis' marriage to his thirteen-twelvemonth-one-time cousin (May 1958), the deaths of Buddy Holly, The Big Bopper and Ritchie Valens in a plane crash (February 1959), the breaking of the Payola scandal implicating major figures, including Alan Freed, in bribery and abuse in promoting private acts or songs (November 1959), the arrest of Chuck Drupe (December 1959), and the death of Eddie Cochran in a car crash (Apr 1960) gave a sense that the initial phase of rock and roll had come to an end.[98]

During the late 1950s and early 1960s, the rawer sounds of Presley, Gene Vincent, Jerry Lee Lewis and Buddy Holly were commercially superseded by a more than polished, commercial way of rock and roll. Marketing oft emphasized the physical looks of the artist rather than the music, contributing to the successful careers of Ricky Nelson, Tommy Sands, Bobby Vee and the Philadelphia trio of Bobby Rydell, Frankie Avalon, Fabian, and Del Shannon, who all became "teen idols."[99]

Some music historians accept too pointed to important and innovative developments that congenital on stone and roll in this menses, including multitrack recording, adult by Les Paul, the electronic treatment of audio by such innovators every bit Joe Meek, and the "Wall of Sound" productions of Phil Spector,[100] connected desegregation of the charts, the rise of surf music, garage rock and the Twist dance craze.[38] Surf rock in particular, noted for the utilize of reverb-drenched guitars, became 1 of the well-nigh popular forms of American rock of the 1960s.[101]

British rock and curl [edit]

Tommy Steele, one of the first British stone and rollers, performing in Stockholm in 1957

In the 1950s, Britain was well placed to receive American rock and roll music and culture.[102] It shared a common language, had been exposed to American culture through the stationing of troops in the state, and shared many social developments, including the emergence of singled-out youth sub-cultures, which in United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland included the Teddy Boys and the rockers.[103] Trad jazz became popular in the U.k., and many of its musicians were influenced past related American styles, including boogie woogie and the blues.[104] The skiffle craze, led by Lonnie Donegan, utilised amateurish versions of American folk songs and encouraged many of the subsequent generation of rock and roll, folk, R&B and crush musicians to kickoff performing.[105] At the aforementioned time British audiences were beginning to run into American stone and roll, initially through films including Blackboard Jungle (1955) and Rock Around the Clock (1956).[106] Both movies featured the Pecker Haley & His Comets hit "Rock Around the Clock", which first entered the British charts in early on 1955 – four months before it reached the US pop charts – topped the British charts later that year and over again in 1956, and helped identify rock and roll with teenage delinquency.[107]

The initial response of the British music industry was to endeavor to produce copies of American records, recorded with session musicians and often fronted by teen idols.[102] More grassroots British rock and rollers shortly began to appear, including Wee Willie Harris and Tommy Steele.[102] During this period American Stone and Curlicue remained ascendant; notwithstanding, in 1958 Great britain produced its first "authentic" rock and gyre song and star, when Cliff Richard reached number 2 in the charts with "Move It".[108] At the same time, TV shows such every bit Six-V Special and Oh Boy! promoted the careers of British rock and rollers similar Marty Wilde and Adam Faith.[102] Cliff Richard and his backing band, the Shadows, were the nearly successful home grown stone and roll based acts of the era.[109] Other leading acts included Baton Fury, Joe Brownish, and Johnny Kidd & the Pirates, whose 1960 hitting song "Shakin' All Over" became a rock and roll standard.[102]

As interest in stone and gyre was get-go to subside in America in the late 1950s and early 1960s, information technology was taken up by groups in major British urban centers like Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham, and London.[110] About the same time, a British blues scene adult, initially led by purist blues followers such as Alexis Korner and Cyril Davies who were directly inspired by American musicians such as Robert Johnson, Muddy Waters and Howlin' Wolf.[111] Many groups moved towards the beat music of rock and curl and rhythm and blues from skiffle, like the Quarrymen who became the Beatles, producing a form of rock and gyre revivalism that carried them and many other groups to national success from about 1963 and to international success from 1964, known in America as the British Invasion.[112] Groups that followed the Beatles included the beat-influenced Freddie and the Dreamers, Wayne Fontana and the Mindbenders, Herman'southward Hermits and the Dave Clark V.[113] Early British rhythm and blues groups with more blues influences include the Animals, the Rolling Stones, and the Yardbirds.[114]

Cultural impact [edit]

Rock and roll influenced lifestyles, way, attitudes, and language.[115] In addition, rock and gyre may take contributed to the civil rights motility because both African-American and white American teens enjoyed the music.[11]

Many early on rock and roll songs dealt with issues of cars, schoolhouse, dating, and habiliment. The lyrics of stone and roll songs described events and conflicts that most listeners could relate to through personal experience. Topics such as sex activity that had generally been considered taboo began to appear in stone and roll lyrics. This new music tried to break boundaries and express emotions that people were actually feeling but had non talked nigh. An awakening began to take identify in American youth culture.[116]

Race [edit]

In the crossover of African-American "race music" to a growing white youth audition, the popularization of rock and roll involved both black performers reaching a white audition and white musicians performing African-American music.[117] Rock and coil appeared at a time when racial tensions in the The states were entering a new phase, with the beginnings of the civil rights motility for desegregation, leading to the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that abolished the policy of "separate but equal" in 1954, only leaving a policy which would be extremely hard to enforce in parts of the U.s..[118] The coming together of white youth audiences and black music in rock and roll inevitably provoked potent white racist reactions within the U.s., with many whites condemning its breaking down of barriers based on color.[11] Many observers saw rock and curl as heralding the fashion for desegregation, in creating a new form of music that encouraged racial cooperation and shared experience.[119] Many authors have argued that early stone and roll was instrumental in the way both white and blackness teenagers identified themselves.[120]

Teen civilization [edit]

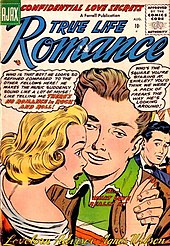

"There'due south No Romance in Rock and Roll" made the encompass of True Life Romance in 1956

Several stone historians have claimed that rock and roll was one of the first music genres to define an historic period group.[121] It gave teenagers a sense of belonging, fifty-fifty when they were lone.[121] Stone and curl is often identified with the emergence of teen civilisation among the first infant boomer generation, who had greater relative affluence and leisure fourth dimension and adopted rock and curl equally office of a distinct subculture.[122] This involved non just music, captivated via radio, tape buying, jukeboxes and Idiot box programs like American Bandstand, but also extended to picture show, clothes, hair, cars and motorbikes, and distinctive language. The youth culture exemplified by rock and gyre was a recurring source of concern for older generations, who worried about juvenile delinquency and social rebellion, particularly because to a large extent rock and roll civilisation was shared by dissimilar racial and social groups.[122]

In America, that concern was conveyed even in youth cultural artifacts such as comic books. In "There's No Romance in Rock and Curlicue" from Truthful Life Romance (1956), a defiant teen dates a rock and roll-loving boy only drops him for i who likes traditional adult music—to her parents' relief.[123] In Britain, where postwar prosperity was more express, rock and curl culture became attached to the pre-existing Teddy Boy movement, largely working form in origin, and eventually to the rockers.[103] Rock and roll has been seen every bit reorienting popular music toward a youth market, as in Dion and the Belmonts' "A Teenager in Love" (1960).[124]

Dance styles [edit]

From its early 1950s beginnings through the early 1960s, rock and scroll spawned new trip the light fantastic toe crazes[125] including the twist. Teenagers found the syncopated backbeat rhythm especially suited to reviving Large Ring-era jitterbug dancing. Sock hops, school and church gym dances, and home basement dance parties became the rage, and American teens watched Dick Clark's American Bandstand to keep up on the latest dance and style styles.[126] From the mid-1960s on, as "rock and roll" was rebranded equally "stone," later dance genres followed, leading to funk, disco, house, techno, and hip hop.[127]

References [edit]

- ^ Farley, Christopher John (July vi, 2004). "Elvis Rocks But He'southward Non the First". Fourth dimension. Archived from the original on August 17, 2013. Retrieved July three, 2009.

- ^ a b c d due east Jim Dawson and Steve Propes, What Was The Start Stone'northward'Whorl Record, 1992, ISBN 0-571-12939-0

- ^ Christ-Janer, Albert, Charles West. Hughes, and Carleton Sprague Smith, American Hymns Former and New (New York: Columbia University Printing, 1980), p. 364, ISBN 0-231-03458-X.

- ^ a b Peterson, Richard A. Creating Country Music: Fabricating Authenticity (1999), p. 9, ISBN 0-226-66285-iii.

- ^ Davis, Francis. The History of the Dejection (New York: Hyperion, 1995), ISBN 0-7868-8124-0.

- ^ "The Roots of Rock 'due north' Gyre 1946–1954". 2004. Universal Music Enterprises.

- ^ a b Kot, Greg, "Rock and ringlet" Archived April 17, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, in the Encyclopædia Britannica, published online 17 June 2008 and also in impress and in the Encyclopædia Britannica Ultimate Reference DVD; Chicago : Encyclopædia Britannica, 2010

- ^ a b Southward. Evans, "The evolution of the Blues" in A. F. Moore, ed., The Cambridge companion to dejection and gospel music (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), pp. 40–42.

- ^ Busnar, Gene, It'southward Rock 'north' Roll: A musical history of the fabulous fifties, Julian Messner, New York, 1979, p. 45

- ^ P. Hurry, M. Phillips, and Chiliad. Richards, Heinemann advanced music (Heinemann, 2001), pp. 153–iv.

- ^ a b c G. C. Altschuler, All shook up: how rock 'n' scroll inverse America (Oxford: Oxford Academy Press U.s., 2003), p. 35.

- ^ "Rock music". The American Heritage Dictionary. Bartleby.com. Archived from the original on May 24, 2009. Retrieved December 15, 2008.

- ^ "Stone and roll". Merriam-Webster'due south Online Dictionary. Merriam-Webster Online. Archived from the original on Apr 27, 2020. Retrieved Dec fifteen, 2008.

- ^ "The United Service Mag". October 22, 2017. Archived from the original on March ten, 2021. Retrieved Nov 19, 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b "Morgan Wright'southward HoyHoy.com: The Dawn of Rock 'n Roll". Hoyhoy.com. May 2, 1954. Archived from the original on June 24, 2011. Retrieved April 14, 2012.

- ^ "Baffled Knight, The (VWML Song Index SN17648)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Archived from the original on March x, 2021. Retrieved February three, 2021.

- ^ "Record Reviews". Billboard. May 30, 1942. Archived from the original on June one, 2021. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

- ^ Billboard, May 30, 1942 Archived March 10, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, page 25. Other examples are in describing Vaughn Monroe'south "Coming Out Political party" in the issue of June 27, 1942, page 76 Archived April 30, 2016, at the Wayback Auto; Count Basie's "It's Sand, Man", in the consequence of October iii, 1942, page 63 Archived June 10, 2016, at the Wayback Motorcar; and Deryck Sampson's "Kansas Urban center Boogie-Woogie" in the event of October ix, 1943, folio 67 Archived June 29, 2016, at the Wayback Motorcar.

- ^ Billboard, June 12, 1943 Archived May 11, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, page 19

- ^ "Alan Freed". Britannica. March four, 2018. Archived from the original on February 5, 2020. Retrieved February three, 2021.

Alan Freed did non coin the phrase he popularized information technology and redefined information technology. In one case slang for sex, information technology came to mean a new course of music. This music had been effectually for several years, but…

- ^ Bordowitz, Hank (2004). Turning Points in Rock and Curlicue . New York, New York: Citadel Press. p. 63. ISBN978-0-8065-2631-vii.

- ^ "Alan Freed". History of Rock. January iv, 2011. Archived from the original on Jan 8, 2021. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- ^ "Ch. 3 "Rockin' Around The Clock"". Michigan s Rock n Roll Legends. June 22, 2020. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

By the centre of the 20th century, the phrase "rocking and rolling" was slang for sex in the black customs but Freed liked the audio of it and felt the words could exist used differently.

- ^ Ennis, Philip (May 9, 2012). The History of American Pop. Greenhaven Publishing LLC. p. 18. ISBN978-1420506723. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- ^ "Alan Freed Dies". Ultimate Classic Stone. Jan 15, 2015. Archived from the original on Feb one, 2021. Retrieved Jan 28, 2021.

- ^ "Stone and Roll Hall of Fame ousts DJ Alan Freed'due south ashes, adds Beyonce's leotards". CNN. August 4, 2014. Archived from the original on Feb 1, 2021. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- ^ "ALAN FREED". Walk of Fame. May 27, 1991. Archived from the original on February 2, 2021. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- ^ "FROM Striking PARADE TO TOP 40". The Washington Mail service. June 28, 1992. Archived from the original on June 1, 2021. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

in the mid- to late '50s with upstarts named Presley, Lewis, Haley, Drupe and Domino

- ^ Hall, Michael K (May 9, 2014). The Emergence of Rock and Scroll: Music and the Rise of American Youth Culture, Timeline. Routledge. ISBN978-0415833134. Archived from the original on June ane, 2021. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bogdanov, Woodstra & Erlewine 2002, p. 1303

- ^ M. T. Bertrand, Race, Rock, and Elvis: Music in American Life (Academy of Illinois Printing, 2000), pp. 21–2.

- ^ R. Aquila, That old-time stone & roll: a chronicle of an era, 1954–1963 (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2000), pp. iv–6.

- ^ J. M. Salem, The late, bully Johnny Ace and the transition from R & B to rock 'due north' roll Music in American life (University of Illinois Press, 2001), p. 4.

- ^ Grand. T. Bertrand, Race, rock, and Elvis Music in American life (University of Illinois Press, 2000), p. 99.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 3, show 55.

- ^ a b Trott, Bill (May 9, 2020). "Rock 'north' roll pioneer Little Richard dies at age 87". Reuters. Archived from the original on Jan 24, 2021. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ A. Bennett, Stone and popular music: politics, policies, institutions (Routledge, 1993), pp. 236–8.

- ^ a b c K. Keightley, "Reconsidering rock" South. Frith, W. Straw and J. Street, eds, The Cambridge companion to popular and rock (Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Press, 2001), p. 116.

- ^ Northward. Kelley, R&B, rhythm and business: the political economy of Blackness music (Akashic Books, 2005), p. 134.

- ^ E. Wald, How the Beatles Destroyed Rock N Roll: An Alternative History of American Pop Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), pp. 111–25.

- ^ Nick Tosches, Unsung Heroes of Rock 'n' Roll, Secker & Warburg, 1991, ISBN 0-436-53203-iv

- ^ Peter J. Silvester, A Left Hand Like God : a history of boogie-woogie piano (1989), ISBN 0-306-80359-3.

- ^ Thousand. Campbell, ed., Popular Music in America: And the Beat out Goes on (Cengage Learning, 3rd edn, 2008), p. 99. ISBN 0-495-50530-7

- ^ P. D. Lopes, The rise of a jazz art globe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), p. 132

- ^ Robert Palmer, "Church building of the Sonic Guitar", pp. xiii-38 in Anthony DeCurtis, Present Tense, Duke University Press, 1992, p. 19. ISBN 0-8223-1265-four.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Louisiana Musicians: Jazz, Blues, Cajun, Creole, Zydeco, Swamp Pop, and Gospel. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. p. 57. ISBN 9780807169322.

- ^ Dance, Helen Oakley, "Walker, Aaron Thibeaux (T-Bone)" The Handbook of Texas Online. Denton: Texas Land Historical Association. Archived from the original on 2008-01-27. Retrieved May fourteen, 2010.

- ^ Michael Campbell & James Brody, Stone and Roll: An Introduction, pages 110–111 Archived August 19, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Michael Campbell & James Brody, Rock and Curl: An Introduction Archived March 11, 2021, at the Wayback Auto, pp. 80–81.

- ^ "Yes, Chuck Drupe Invented Rock 'north' Roll -- and Singer-Songwriters. Oh, Teenagers Too". Foodservice and Hospitality magazine. March 22, 2017. Archived from the original on February 27, 2021. Retrieved August 2, 2020.

Of course similar musics would have sprung up without him. Elvis was Elvis before he'd ever heard of Chuck Berry. Charles' proto-soul vocals and Brown'due south everything-is-a-pulsate were innovations as profound equally Berry'south. Bo Diddley was a more accomplished guitarist.

- ^ Williams, R (March 18, 2015). "Sister Rosetta Tharpe: the godmother of rock 'north' scroll". Archived from the original on July 8, 2017. Retrieved December xvi, 2016.

- ^ Beaty, James. "RAMBLIN' Round: Hank Williams: Kicking open that rock 'n' curl door". McAlester News-Capital. Archived from the original on March ten, 2021. Retrieved November 5, 2020.

- ^ Robert Palmer, "Church of the Sonic Guitar", pp. thirteen–38 in Anthony DeCurtis, Nowadays Tense, Duke University Press, 1992, p. 19. ISBN 0-8223-1265-four.

- ^ Jimmy Preston at AllMusic

- ^ a b Chiliad. Campbell, ed., Popular Music in America: and the Trounce Goes on (Boston, MA: Cengage Learning, third edn., 2008), ISBN 0-495-50530-7, pp. 157–8.

- ^ a b Gilliland 1969, bear witness 5, show 55.

- ^ Robert Palmer, "Stone Begins", in Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock and Curlicue, 1976/1980, ISBN 0-330-26568-7 (UK edition), pp. 3–14.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie. Nascence of Rock & Roll at AllMusic. Retrieved March 24, 2012.

- ^ Collis, John (2002). Chuck Berry: The Biography. Aurum. p. 38. ISBN9781854108739. Archived from the original on May 26, 2016. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- ^ DeCurtis, Anthony (1992). Present Tense: Rock & Curl and Culture (four. impress. ed.). Durham, N.C.: Duke Academy Printing. ISBN0822312654. Archived from the original on June 17, 2016. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

His get-go venture, the Phillips label, issued only one known release, and it was one of the loudest, most overdriven, and distorted guitar stomps always recorded, "Boogie in the Park" by Memphis i-homo-band Joe Hill Louis, who cranked his guitar while sitting and banging at a rudimentary pulsate kit.

- ^ Aswell, Tom (2010). Louisiana Rocks! The True Genesis of Stone & Roll. Gretna, Louisiana: Pelican Publishing Company. pp. 61–5. ISBN978-1589806771. Archived from the original on November 22, 2016. Retrieved Oct 17, 2015. .

- ^ Dave, Rubin (2007). Inside the Dejection, 1942 to 1982. Hal Leonard. p. 61. ISBN9781423416661. Archived from the original on April 24, 2016. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- ^ Robert Palmer, "Church of the Sonic Guitar", pp. xiii–38 in Anthony DeCurtis, Nowadays Tense, Duke Academy Press, 1992, pp. 24–27. ISBN 0-8223-1265-iv.

- ^ P. Buckley, The rough guide to rock (Rough Guides, 3rd edn., 2003), p. 21.

- ^ "Bo Diddley". The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum. Archived from the original on Feb 12, 2011. Retrieved October 27, 2008.

- ^ "Bo Diddley". Rolling Stone. 2001. Archived from the original on August 22, 2012. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ Brownish, Jonathan (June iii, 2008). "Bo Diddley, guitarist who inspired the Beatles and the Stones, dies anile 79". The Independent. Archived from the original on March 22, 2020. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ Redd, Lawrence N. (March 1, 1985). "The Blackness Perspective in Music". Wall Street Journal. 13 (1): 31–47. doi:10.2307/1214792. JSTOR 1214792. Archived from the original on May 25, 2019. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

past Lawrence North. Redd

- ^ Leight, Elias (October 26, 2017). "Paul McCartney Remembers 'Truly Magnificent' Fats Domino". Rollingstone.com. Archived from the original on Nov 25, 2020. Retrieved March fifteen, 2021.

- ^ Palmer, Robert (Apr 19, 1990). "The 50s: A Decade of Music That Inverse the Globe". Rollingstone.com. Archived from the original on February 22, 2021. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, shows vii–viii.

- ^ a b c "Stone and Roll Pilgrims: Reflections on Ritual, Religiosity, and Race at Rockabilly at AllMusic. Retrieved August 6, 2009.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, evidence vi.

- ^ Sagolla, Lisa Jo (2011). Rock 'N' Curlicue Dances of the 1950s. The American Dance Floor. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood. p. 17. ISBN978-0-313-36556-0.

- ^ "Granville'due south Bill Flagg pioneered rockabilly". masslive.com. Archived from the original on June ane, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2017.

- ^ Elvis at AllMusic. Retrieved August 6, 2009.

- ^ Nib Haley at AllMusic. Retrieved August 6, 2009.

- ^ P. Humphries, The Consummate Guide to the Music of The Beatles, Volume 2 (Music Sales Group, 1998), p. 29.

- ^ F. W. Hoffmann and H. Ferstler, Encyclopedia of recorded sound, Volume 1 (CRC Press, 2nd edn., 2004), pp. 327–8.

- ^ a b c d due east f Bogdanov, Woodstra & Erlewine 2002, pp. 1306–7

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 5, track 3.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 13.

- ^ a b Gilliland 1969, show four, track 5.

- ^ Ennis, Philip H. (1992), The 7th Stream – The Emergence of Rocknroll in American Pop Music, Wesleyan Academy Press, p. 201, ISBN 978-0-8195-6257-9

- ^ R. Aquila, That sometime-time stone & coil: a relate of an era, 1954–1963 (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2000), p. 6.

- ^ C. Deffaa, Blue rhythms: vi lives in rhythm and blues (Chicago: Academy of Illinois Press, 1996), pp. 183–iv.

- ^ J. V. Martin, Copyright: current bug and laws (Nova Publishers, 2002), pp. 86–8.

- ^ Grand. Lichtenstein and 50. Dankner. Musical gumbo: the music of New Orleans (Westward.W. Norton, 1993), p. 775.

- ^ R. Carlin. Country music: a biographical lexicon (Taylor & Francis, 2003), p. 164.

- ^ R. Aquila, That old-time rock & roll: a chronicle of an era, 1954–1963 (Chicago: University of Illinois Printing, 2000), p. 201.

- ^ G. C. Altschuler, All shook upwardly: how rock 'northward' roll changed America (Oxford: Oxford University Printing US, 2003), pp. 51–two.

- ^ R. Coleman, Blue Monday: Fats Domino and the Lost Dawn of Stone 'due north' Roll (Da Capo Press, 2007), p. 95.

- ^ D. Tyler, Music of the postwar era (Greenwood, 2008), p. 79.

- ^ C. 50. Harrington, and D. D. Bielby., Pop culture: production and consumption (Wiley-Blackwell, 2001), p. 162.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 7, track four.

- ^ D. Hatch and S. Millward, From blues to rock: an belittling history of pop music (Manchester: Manchester University Press ND, 1987), p. 110.

- ^ M. Campbell, Pop Music in America: And the Shell Goes on: Popular Music in America (Publisher Cengage Learning, 3rd edn., 2008), p. 172.

- ^ M. Campbell, ed., Popular Music in America: And the Beat Goes on (Cengage Learning, third edn., 2008), p. 99.

- ^ Middleton, Richard; Buckley, David; Walser, Robert; Laing, Dave; Manuel, Peter (2001). "Popular | Grove Music". doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.46845. ISBN978-1-56159-263-0. Archived from the original on May 22, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2018.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 21.

- ^ "Surf Music Genre Overview – AllMusic". AllMusic. Archived from the original on October 29, 2019. Retrieved Baronial 22, 2014.

- ^ a b c d eastward Unterberger, Richie. British Stone & Gyre Before the Beatles at AllMusic. Retrieved June 24, 2009.

- ^ a b D. O'Sullivan, The Youth Culture (London: Taylor & Francis, 1974), pp. 38–9.

- ^ J. R. Covach and G. MacDonald Boone, Understanding Rock: Essays in Musical Analysis (Oxford: Oxford Academy Press, 1997), p. 60.

- ^ M. Brocken, The British folk revival, 1944–2002 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2003), pp. 69–80.

- ^ V. Porter, British Cinema of the 1950s: The Turn down of Deference (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), p. 192.

- ^ T. Gracyk, I Wanna Be Me: Stone Music and the Politics of Identity (Temple University Printing, 2001), pp. 117–18.

- ^ D. Hatch, S. Millward, From Blues to Rock: an Analytical History of Pop Music (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1987), p. 78.

- ^ A. J. Millard, The electric guitar: a history of an American icon (JHU Press, 2004), p. 150.

- ^ Mersey Beat – the founders' story Archived February 24, 2021, at the Wayback Automobile.

- ^ V. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra, S. T. Erlewine, eds, All Music Guide to the Dejection: The Definitive Guide to the Dejection (Backbeat, tertiary edn., 2003), p. 700.

- ^ British Invasion at AllMusic. Retrieved August ten, 2009.

- ^ Robbins, Ira A. (February seven, 1964). "British Invasion (music)". Britannica.com. Archived from the original on February 17, 2011. Retrieved April xiv, 2012.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie (1996). "Blues rock". In Erlewine, Michael (ed.). All music guide to the blues : The experts' guide to the best blues recordings. All Music Guide to the Blues. San Francisco: Miller Freeman Books. p. 378. ISBN0-87930-424-3.

- ^ 1000. C. Altschuler, All shook up: how rock 'n' roll changed America (Oxford: Oxford University Press U.s.a., 2003), p. 121.

- ^ Schafer, William J. Rock Music: Where It'southward Been, What It Ways, Where It's Going. Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing House, 1972.

- ^ M. Fisher, Something in the air: radio, rock, and the revolution that shaped a generation (Marc Fisher, 2007), p. 53.

- ^ H. Zinn, A people's history of the Usa: 1492–nowadays (Pearson Instruction, 3rd edn., 2003), p. 450.

- ^ Chiliad. T. Bertrand, Race, rock, and Elvis (University of Illinois Press, 2000), pp. 95–half-dozen.

- ^ Carson, Mina (2004). Girls Stone!: Fifty Years of Women Making Music. Lexington. p. 24.

- ^ a b Padel, Ruth (2000). I'm a Man: Sex, Gods, and Stone 'n' Ringlet. Faber and Faber. pp. 46–48.

- ^ a b M. Coleman, L. H. Ganong, K. Warzinik, Family Life in Twentieth-Century America (Greenwood, 2007), pp. 216–17.

- ^ Nolan, Michelle. Love on the Racks (McFarland, 2008) p.150

- ^ Lisa A. Lewis, The Adoring Audition: Fan Culture and Popular Media (Routledge, 1992), p. 98.

- ^ sixtiescity.com Archived March 24, 2012, at the Wayback Motorcar Sixties Dance and Dance Crazes

- ^ R. Aquila, That old-time rock & roll: a chronicle of an era, 1954–1963 (University of Illinois Press, 2000), p. 10.

- ^ Campbell, Michael; Brody, James (1999). Rock and Gyre: An Introduction. New York, NY: Schirmer Books. pp. 354–55.

Sources [edit]

- Bogdanov, V.; Woodstra, C.; Erlewine, Due south. T., eds. (2002). All Music Guide to Rock: the Definitive Guide to Stone, Pop, and Soul (tertiary ed.). Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books. ISBN0-87930-653-X.

- Rock and Roll: A Social History, by Paul Friedlander (1996), Westview Press (ISBN 0-8133-2725-3)

- "The Stone Window: A Way of Agreement Rock Music" past Paul Friedlander, in Tracking: Popular Music Studies Archived September 23, 2006, at the Wayback Car, Volume I, number i, Spring, 1988

- The Rolling Rock Encyclopedia of Rock & Scroll by Holly George-Warren, Patricia Romanowski, Jon Pareles (2001), Fireside Press (ISBN 0-7432-0120-v)

- The Audio of the City: the Rise of Stone and Roll, past Charlie Gillett (1970), Eastward.P. Dutton

- Gilliland, John (1969). "Hail, Hail, Stone 'n' Roll: The rock revolution gets underway" (sound). Pop Chronicles. Academy of Northward Texas Libraries.

- The Fifties by David Halberstam (1996), Random House (ISBN 0-517-15607-v)

- The Rolling Rock Illustrated History of Rock and Ringlet : The Definitive History of the Most Of import Artists and Their Music by editors James Henke, Holly George-Warren, Anthony Decurtis, Jim Miller (1992), Random Business firm (ISBN 0-679-73728-6)

External links [edit]

- Rock music at Curlie

- The Camp Meeting Jubilee 1910 recording

- The Smithsonian's history of the electric guitar

- History of Stone

- Youngtown Rock and Roll Museum – Omemee, Ontario

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rock_and_roll

0 Response to "Was Rock and Roll Responsible for Americaã¢â‚¬â„¢s Traditional Family, Sexual, and Racial Customs"

Post a Comment