Ta nehisi Coates the Lost Cause Rides Again

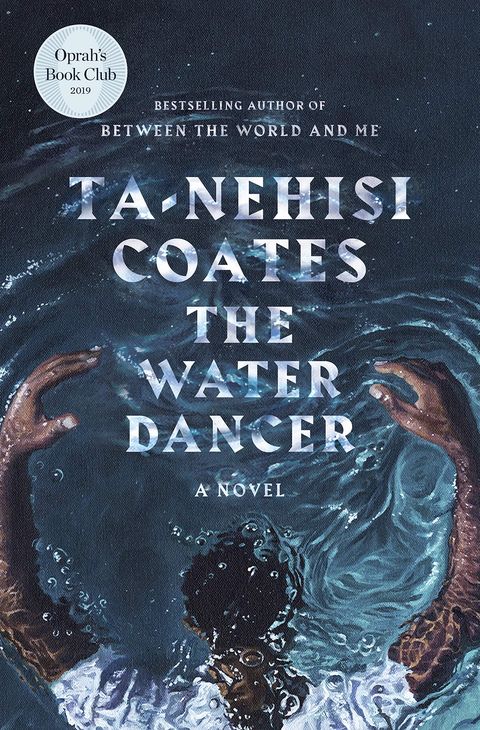

Oprah announced today that her first choice in the newly-forged partnership between Oprah's Book Club and Apple tree is Ta-Nehisi Coates's debut novel, The Water Dancer. This remarkable tale of the sojourn of an enslaved human on the road to freedom "pierced my soul," Oprah says. "I oasis't felt this mode since I offset read Beloved."

The odyssey chronicles an enslaved homo's journeying out of bondage aided past a superpower he didn't know he had. In the October issue of O, Coates revealed to O's books editor Leigh Haber the inspiration backside his latest piece of work—and how the impulse to create this character and interweave history, fantasy, and symbolism, goes all the way back to his babyhood.

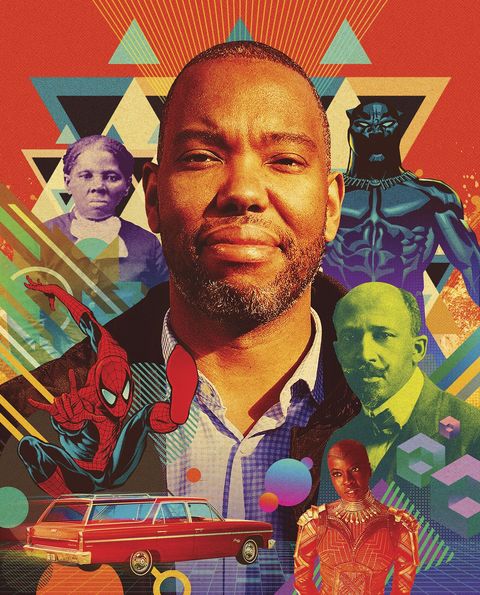

A recipient of the National Book Laurels and a MacArthur "genius" grant, Ta-Nehisi Coates, 44, has explored the importance of archetypes, particularly every bit they relate to the African American story, in his previous books, The Cute Struggle, Between the World and Me, and Nosotros Were Eight Years in Power. But he's been thinking about how myths mold our perspective pretty much his whole life.

More From Oprah Daily

At 5, he says, "I was in the back seat of my parents' red station wagon, talking about my favorite television show, The Tarzan/Lone Ranger/Zorro Risk Hr, and I told my dad how much I loved Tarzan." His father, Paul (dubbed Conscious Homo past his son in The Beautiful Struggle), was skeptical.

Store Now on Apple tree Books

Shop Now on Amazon

Equally a member of the Black Panther Party and devotee of obscure works virtually African and African American history, Paul never missed a run a risk to school his son virtually his heritage. In this case, he wanted Ta-Nehisi to sympathise the subtext of the Tarzan legend, and to know that his dad objected to this white man in "the jungles of Africa" interim like a hero among "savages."

Paul told Ta-Nehisi he wouldn't be allowed to watch Tarzan until he could run into for himself the racist undertones—that there was more than to it than the adventures of a guy in a loincloth swinging from vine to vine. In fact, his son would be barred from watching whatever TV for a week while he worked out why the story shouldn't be taken at face value.

What could perchance be wrong with Tarzan?, Coates recalls thinking. Over the next few days, he and his father debated. Paul shared books and images for context and expounded on why but certain types of people are portrayed as heroes in our history and literature. What Coates now calls the Cognition started to sink in. He kept watching Tarzan simply returned once again and again to his father'due south words. "Those were my first deep lessons," he says.

Coates was an early reader—his mom was a schoolteacher who instructed him herself. By the time he got to start class, he remembers "wondering why everyone read and so deadening." At home in his bedroom, he pored over a set of Childcraft encyclopedias and spent hours at the Enoch Pratt Free Library, winning a prize for getting through the most books in a summer. "Schoolhouse," he says, "was something I did to continue people off my back. Learning was something I did on my own."

Coates'due south parents allowed him to take action figures simply with Black skin—for instance, Roadblock and Stalker, the Black soldiers who back up G.I. Joe. He besides loved comic books; superheroes' exploits transported him out of Due west Baltimore, where kids worried near getting beaten up or shot. ("I knew that to exist agape while on the manner to school was deeply incorrect," he writes in The Cute Struggle.) Though at that place were few Black characters in the Marvel universe apart from Black Panther, Falcon, and Luke Cage, Coates detected in the X-Men and especially Spider-Man an underdog quality he identified with. "I never thought of Peter Parker as white," he says.

This content is imported from poll. You may exist able to detect the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

"If anything, I related him to Black people because he was poor and ever trying to do the right affair, though most of the fourth dimension in that location was no reward waiting for him at the end. It wasn't most skin colour. Information technology was about where you existed in club."

Comics stretched his vocabulary, Coates says. "They're big and boisterous and use a kind of high linguistic communication you don't run across every day." Hip-hop and rap also shaped him: "It was the first identify I really retrieve being struck past the fact that you could organize words rhythmically and create cute feelings. I wanted to practice that. I estimate that tied into some bequeathed ideas about drumming and oral history." Only it was in the work of W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington, and on the pages of the Black Classic Press books his father brought dorsum to print, that Coates found his nearly solid footing. As he puts it: "I was anchored."

After attending Howard University, he spent years equally a freelance journalist and subsequently as a staff writer for the Village Vox, then the Atlantic. He became an outspoken critic of a society in which the "falsehood of race" burdens Black men and women. In 2009, he went on what he calls a Civil War bender, devouring everything he could observe on the topic; he considers the projection ongoing.

He'd heard people argue that the conflict wasn't really about slavery; that Robert E. Lee represented a grand, gallant Confederacy, with the Old Southward a romantic lost cause. But after a close reading of the Ordinances of Secession and other documents, he knew there was no greyness area: If people chose to believe the war hadn't been most keeping or freeing slaves, "it was because they didn't want to let the facts violate myth," he says. "They didn't desire to let go of heroes who'd organized the way they saw things."

Black Panther was a revelation for Black people around the world—it made us more than enlightened.

Coates remained a fan of superheroes and their adventures, and in 2016, his revival of the Blackness Panther character for a new graphic comic series was published; in 2018, Ryan Coogler'southward T'Challa-centric movie Black Panther premiered to frenzied acclaim. In the fictional state of Wakanda, African Americans saw relatable myths and superheroes on a grand scale. "Black Panther was a revelation for Blackness people effectually the world," says Coates. "It made united states of america more aware of the role heroes play and who deserves to be seen equally beauteous. White heroes have been given that kind of large-upkeep treatment for decades."

In his astonishing new work, the novel The Water Dancer, Hiram Walker is a hero in his own right—built-in into chains and without memory of his mother, until he finds a hidden ability enabling him to connect with the by. The feel lifts him out of near-catatonic despair and into an awakened state where "fifty-fifty in the darkness some role of me smiled." Hiram learns to draw strength from those who came before.

He even joins forces with Harriet Tubman, a.grand.a. Moses, whose soul was "scarred, but not cleaved, by the worst of slavery." Hiram "grew stronger, grew faster.... And this began not with the body, but the mind." Coates's "beautiful struggle"—to reconcile the present with the past, youthful idealism with difficult-won realism, fact with myth—has given us an electric retelling of an old story. This modern masterpiece enables united states of america to comprehend what information technology must exist to have never known freedom and risk everything to attain it.

For more stories similar this, sign up for our newsletter.

This content is imported from OpenWeb. You may exist able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their spider web site.

Source: https://www.oprahdaily.com/entertainment/books/a28984934/ta-nehisi-coates-interview-the-water-dancer-oprah-book-club/

0 Response to "Ta nehisi Coates the Lost Cause Rides Again"

Post a Comment